The

exchange rates for the currencies of most developed countries are

'free floating'. That is the value of the currency is determined by

demand and supply in the

foreign exchange market.

The foreign exchange market works to a great extent like any other market. The price of the currency rises when demand for the currency rises or supply falls. On the level of trade this means that when anyone wants to

import, say British, goods they demand the pounds they need to pay British firms who supply them. There is then a market in pounds with those buying British goods and services demanding pounds and Britons selling pounds in order to gain the currency they need to import goods and services from other nations.

There is another aspect to currency markets however. The currency itself can be an

asset and also a medium to invest in another country. Some people will want to invest their money in a country to get a higher return than they could elsewhere. Others will hold currency in order to make a

capital gain, that is buy low and sell high.

This second reason to buy and sell currency makes the

expectation of the future value of a currency very important. If you expect the value of a currency to fall you sell it before it does, this avoids a

capital loss and prevents the advantage of getting a better interest rate being wiped out by the falling value of the currency.

Since Britain voted to leave the EU (in a travesty of a referendum) the pound has been falling in value.

The Pound against the US$ October 2015 to October 2016

The sharp fall on the day after the Brexit vote on June 23rd is clearly visible and so is the continued fall of the past two weeks.

The article linked below gives some reasons for this in particular. In summary these are:

* Concerns that the UK economy will grow more slowly.

* Concerns that the UK will not have free access to the EU single market after Brexit

* That interest rates will not rise in the UK to prevent further domestic contraction (relative interest rates fall)

* Concern that holding pounds will lead to a capital loss, due to the above reasons, so best to sell now.

Note the importance of expectations and risk in this system. It is crucial to behaviour.

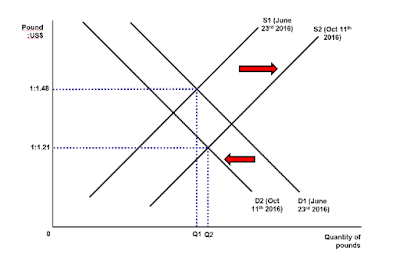

The diagram below shows how the foreign exchange market for the pound might have behaved since June. Fewer buyers (who buys a currency with a way to fall leaving just 'trade' demand) D1 to D2 and more sellers (investors leaving for safer currencies) S1 to S2.

Note the links within the article that are worth exploring.

As this story is about the UK pound (GBP) this is most useful for IB students on how the floating exchange rate mechanism works. However VCE students should realise that the Australian dollar has the same floating system.