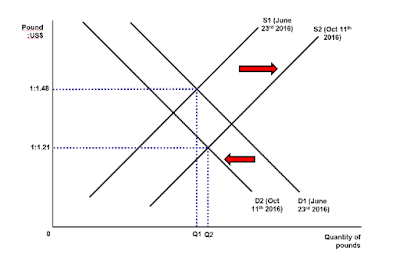

The UK has recently seen a 20% fall in their currency, the pound (GBP), against the dollar. Some now expect there to be a revival in British manufacturing and a rise in growth and jobs as a result. It is unlikely.

Of course a depreciation of a currency does make exports cheaper. There will be a rise in exports as a result, but there are many considerations before we can say this is unambiguously good.

Firstly the Current Account of the Balnance of Payments will only improve if the Marshall-Lerner conditions are met and the sum of the price elasticities of exports and imports sum to more than one. They will.

Mentioning imports is of course more than important. Import prices will rise with a depreciation and so will inflation. If firms rely on imported components then their costs will rise too. And let's not forget the humble holiday maker - it's not more expensive to holiday abroad. Those who champion UK manufacturing will say 'holiday in the UK', but how much rain and fish and chips can they really stand?

There is also the problem that depreciation only masks deeper problems, such as fundamentally low productivity, poor design and low quality. Temporary relief is at best provided by a depreciation which can easily be reversed. Further it isn't possible for all countries to depreciate their currency because exchange rates are a relative measure of value. A series of competitive devaluations will be at best inflationary and fruitless.

The most sensible thing ever said about depreciations is that 'there are just more questions' once they have occurred.

The article below examines the likely effect of the UK's recent depreciation.

Primarily an example for IB students it raises very important questions about the pros and cons of floating exchange rates and the likely effects of exchange rate movements. Never forget the Marshall-Lerner conditions for HL candidates. VCE students will however recognise the effects of the changing value of the Australian dollar and the likely effects on the Australian economy and the macroeconomic goals.